Complying with the new regulations is going to be challenging even for the OEMs that have a robust mineral sourcing strategy

On 7 August 2022, Democrats in the US Senate passed the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which aims to not only take control of rising inflation by reducing the fiscal deficit but also invest in domestic manufacturing of renewable energy and electric vehicles (EVs), secure the necessary supply chain, and cut down the carbon footprint by roughly 40% by 2030.

The proposal made within the purview of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) expects to raise about USD739 billion and invest about USD433 billion to reduce the total deficit by more than USD300 billion, according to an official government document. While the biggest component that is expected to raise the revenue for the US government—if the IRA passes through later this month and becomes legislation—is the flat 15% corporate minimum tax that would be levied on all companies with annual earnings of USD1 billion or more (raising about USD313 billion), it aims to historically make the biggest investment the US has ever made on energy security and climate change, which would be to the tune of USD369 billion over the next 10 years.

Although the contours of the IRA 2022 are not only limited to the manufacturing of clean vehicles, let’s focus on how the proposed measures would impact the upcoming zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) ecosystem.

First of all, the IRA 2022 limits the maximum retail price up to USD80,000 for electric vans, electric SUVs, and electric pickup trucks to remain eligible for the tax credit. For other EV categories, including sedans and hatchbacks, the retail price is capped at USD55,000. Of course, the underlying requirement is that the vehicles are locally manufactured with final assembly within North America. Reportedly, this measure has drawn criticism from the upcoming EV startups such as Rivian and Fisker.

Besides including the EVs and the plug-in hybrids (PHEVs), the IRA 2022 also includes the fuel-cell motor vehicles for the first time.

Secondly, while the newly proposed regulation continues to offer a tax credit of USD7,500, which was first authorized in 2008–09 with the intention of accelerating EV adoption in the US, it has added new conditions by equally splitting the eligibility of availing this credit under two notable heads—critical minerals used in the EV batteries and the battery components. As a result, for an electric car to be eligible for the tax credit of USD7,500, the model must meet the criteria set under the requirements on the critical materials as well as the components used in its batteries to avail credit of USD3,750 each.

The IRA 2022 puts out a list of qualifying battery components such as electrode active materials, battery cells, and battery modules. Additionally, the proposed regulation also lists several applicable critical minerals such as aluminum, beryllium, cerium, chromium, cobalt, graphite, lithium, manganese, nickel, tungsten, among several others with a primary intent to shore up local manufacturing of the EV ecosystem in the US through the decade.

For a battery powered electric vehicle (BEVs and PHEVs) to meet the requirements for the critical minerals used in its battery to be eligible for the credit of USD3,750, it must ensure that the applicable minerals (as defined in the official document) must be extracted or processed in the US, or in any other country with which the US has a free trade agreement (FTA) or recycled in North America. The percentage of the value of these applicable minerals used in the battery must be at least 40% for vehicles sold before 1 January 2024, 50% for vehicles sold in calendar year (CY) 2024, 70% for vehicles sold in CY 2026, and 80% for vehicles sold thereafter.

Similarly, on the battery components, the IRA 2022 proposes two key statutory requirements—the specified components must be manufactured or assembled in North America as well as the percentage of the value of these battery components must be equal to or greater than 50% in vehicles sold before 1 January 2024. As proposed, the applicable percentage on the value of components used in the batteries will increase by 10% each year, climbing up to 100% for vehicles sold in the US from CY 2029.

It is evident that the IRA 2022 aims to shore up local manufacturing of clean vehicles along with incentivizing the companies to pull their supply chain ecosystem to the US through the decade in a phase-wise manner. The focus remains mainly on securing the local production of batteries as well as the critical minerals that are used in producing the same, along with other components such as electric motors that use the rare-earth minerals.

The US government, which aims to reduce its dependency on the Asian countries, mainly China, amid the global rush to cut carbon footprints and transition to electric mobility, had termed securing adequate supply of critical battery materials as well as semiconductors as a matter of national security in 2021. The IRA 2022 further builds upon that government agenda, which while shoring up domestic manufacturing also aims to create employment at home.

The new measures also eliminate the earlier sales cap of 200,000 units wherein the eligibility for the USD7,500 tax credit would phase-out once the vehicle manufacturer surpasses the cumulative sales mark. Reportedly, the condition is knocked off primarily to ensure that the models sold by the established EV makers such as Tesla, General Motors (GM), and others continue to remain eligible in the market, maintaining healthy competition and supporting widespread EV adoption. Interestingly, while Tesla had amassed cumulative sales of 200,000 EVs in 2018, the BEV and PHEV models from GM and Toyota too would have become ineligible had the earlier rule prevailed.

According to a recent preliminary report titled ‘The Climate and Energy Impacts of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022’ released by the Princeton University’s Zero Lab, beyond the direct emissions reduction impacts of the policies, the IRA contains important policy measures and programs that will encourage innovation and maturation of nascent advanced energy industries, build US clean energy manufacturing and supply chains, and drive investments.

“The Act builds on the demonstration and hubs funding in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law by providing early market deployment opportunities over the next decade that will drive innovation and maturation of important nascent clean technologies that need to be ready for wide-scale deployment in the 2030s and 2040s, including clean hydrogen, carbon capture, zero-carbon liquid fuels, direct air capture, advanced nuclear and geothermal energy, and more. These technologies all have access to robust deployment subsidies (many for the first time) that are likely to have a catalytic impact,” quotes the report, which analyses the IRA 2022 under Princeton University’s Rapid Energy Policy Evaluation and Analysis Toolkit or REPEAT project.

“The Act contains robust support for the development of American manufacturing of solar, wind, battery and electric vehicle components and assembly as well as critical minerals processing. The bill ties bonus tax incentives for clean electricity and credits for consumer clean vehicles purchases to domestic content sourcing standards, providing strong demand for US materials and manufacturing. It also provides USD2 billion in grants and USD30 billion in loans to retool American auto manufacturing to produce clean vehicles and USD37 billion in new tax credits to spur investment in America’s capacity to produce and assemble wind and solar PV components, batteries and clean vehicles, and process critical minerals. An additional USD0.5 billion is also appropriated for the President to use the Defense Production Act to build American supply chains for heat pump and battery manufacturing, critical minerals, and other strategic priorities. Those policies are important to expand supply chains and enable rapid scale-up of these technologies, and they will also create hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs across the country,” the Princeton University’s Zero Lab said in its detailed evaluation of the IRA 2022.

Will new rules for critical battery minerals, components restrict eligibility?

Whether the newly proposed regulations that impose specific conditions on the sourcing of battery critical minerals as well as battery components would limit the eligibility of electric cars to qualify for the tax credit remains the burning question for EV supply chain stakeholders. If the battery cells and modules are locally produced in the US, what happens if the battery maker does not source critical materials as specified under the IRA 2022 from the US or other countries with FTAs with the US?

Notably, the new regulation demands that the critical battery materials are sourced locally in the US or from the countries such as Australia, Canada, Chile, Morocco, South Korea, and others that have a FTA with the US to remain eligible for the tax credit.

In the recent past, a number of big-ticket investments were announced by several global battery makers looking to expand production capacity and build additional gigafactories in the US. For example, Stellantis and its battery partner Samsung SDI announced in May 2022 that their joint venture company will set up a USD2.5-billion gigafactory in the Indiana region. The planned gigafactory, which is slated to begin commercial operations in 2025, will have an initial annual production capacity of 23GWh, scalable up to 33GWh over the next few years.

Interestingly, Samsung SDI, which had launched a new brand called PRiMX late in 2021 to represent its premium battery technology and strict quality control, has an ongoing five-year agreement with Glencore to source cobalt hydroxide as well as a multi-year agreement with Umicore to source NMC (nickel manganese cobalt) cathode materials (produced in South Korea).

Meanwhile, China’s largest battery maker CATL, which is reportedly looking to set up a USD5-billion plant in the US, has recently signed a non-binding memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Ford Motor Company. Ford said that it plans to source lithium iron phosphate or LFP battery packs from CATL, adding a new chemistry in its battery mix, which is also estimated to provide the automaker material savings of up to 15% compared with the NCM batteries. The agreement with CATL entails sourcing of LFP batteries to begin in 2023 for Ford’s Mustang Mach-E models and in early 2024 for the F-150 Lightning pickup truck. While Ford’s plan entails localizing and using up to 40GWh of LFP battery capacity in North America starting in 2026, it is expected that CATL may source the LFP battery materials from China, which dominates in the LFP supply chain.

Does this mean that Ford’s EVs with CATL’s LFP batteries may become ineligible for tax credits?

“LFP cathode and upstream material supply chain is vastly dominated by China. If Ford wants to benefit from the tax credits, it should convince CATL to bring the cathode production to North America to comply with the “component" requirement. Fulfilling the “critical mineral” requirement is even more difficult as there’s no LFP upstream material supply chain in place in North America,” S&P Global Mobility’s battery experts Ali Adim Hafshejani and Jay Hwang said.

“The IRA 2022 might disincentivize the LFP chemistry as one the value propositions of LFP is lower cost, however fulfilling the IRA requirements is more difficult for this chemistry compared to NCM or NCA due to the dominance of China on its supply chain. Therefore, if opting for LFP would mean losing the tax credit, LFP will lose its low-cost advantage,” they added.

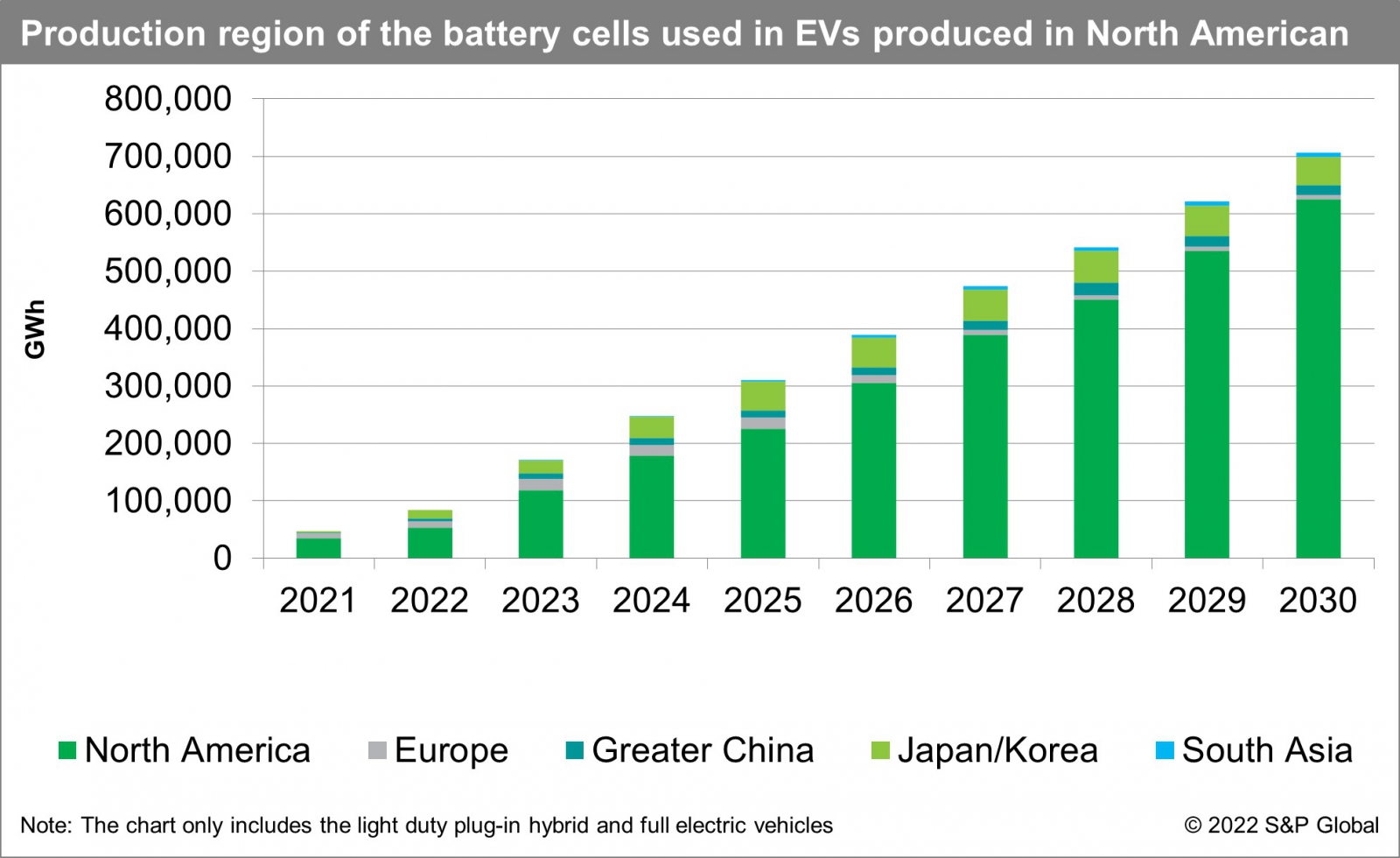

Moreover, Adim and Hwang estimate that the major global battery suppliers that have recently announced investments in the US or are mulling the same may be incentivized for local cell production even further under the IRA 2022 as the proposed regulations consider a tax break of up to USD35/kWh for the battery cell manufacturers. “As the cells that can satisfy the IRA requirements will be on high demand, it would make sense for the cell makers to push their material suppliers to move their production to North America,” they point out.

Additionally, commenting on how the new act would impact the specific battery component suppliers, they said, “There is already a great growth in the cell and module production in North America. However, the local cathode and anode production is currently insignificant. As the active materials are the most expensive components of the batteries, satisfying the requirement would mean local cathode and anode production, especially as we will approach 2028 that has a 100% threshold for local sourcing. The 10% tax break will incentivize the electrode producers to make investments in North America in addition to a guaranteed demand from the already incentivized car industry. The tax break will vastly benefit CAM suppliers such as Posco or Umicore who already had plans for the production in Canada. As the competition for such locally produced material will increase, it will be crucial for the OEMs to strengthen their positioning by forming JVs or partnerships.”

That said, the S&P Global Mobility’s senior research analysts for electric mobility and battery estimate that in general, complying with this regulation (IRA 2022) is going to be challenging even for the OEMs that have a robust mineral sourcing strategy such as Tesla.

“In terms of mineral resources, North America is not on top of the list. Canada has nickel resources such as Sudbury mine as well as natural graphite. United States has minor lithium production in Silver Peak with a capacity of 5000 tons of lithium carbonate per year, which is enough to make only 75,000 vehicles. A successful strategy should exploit these resources as much as possible. Meanwhile, China dominates the battery material refining production capacities. The IRA act considers 10% tax break for the battery mineral and electrode processing that will incentivize local investment for the mineral processing and electrode manufacturing,” Adim and Hwang said, adding that “in terms of the OEM sourcing strategies, the IRA act would mean OEMs should revisit some their partnerships. For instance, in the Tesla supplier list, there are few who fulfill the requirements. This might lead to bifurcation of the strategy: one strategy for the volume production focusing the major producers, such as Indonesia for nickel and DRC for Cobalt, and another strategy tailored for the tax credit. The latter will be realized by either partnership or investment in local producers or the countries with whom the US has FTA.”

Author: Amit Panday, senior research analyst, battery, S&P Global Mobility

With inputs from S&P Global Mobility's Sr Technical Research Analysts Ali Adim Hafshejani and Jay Hwang